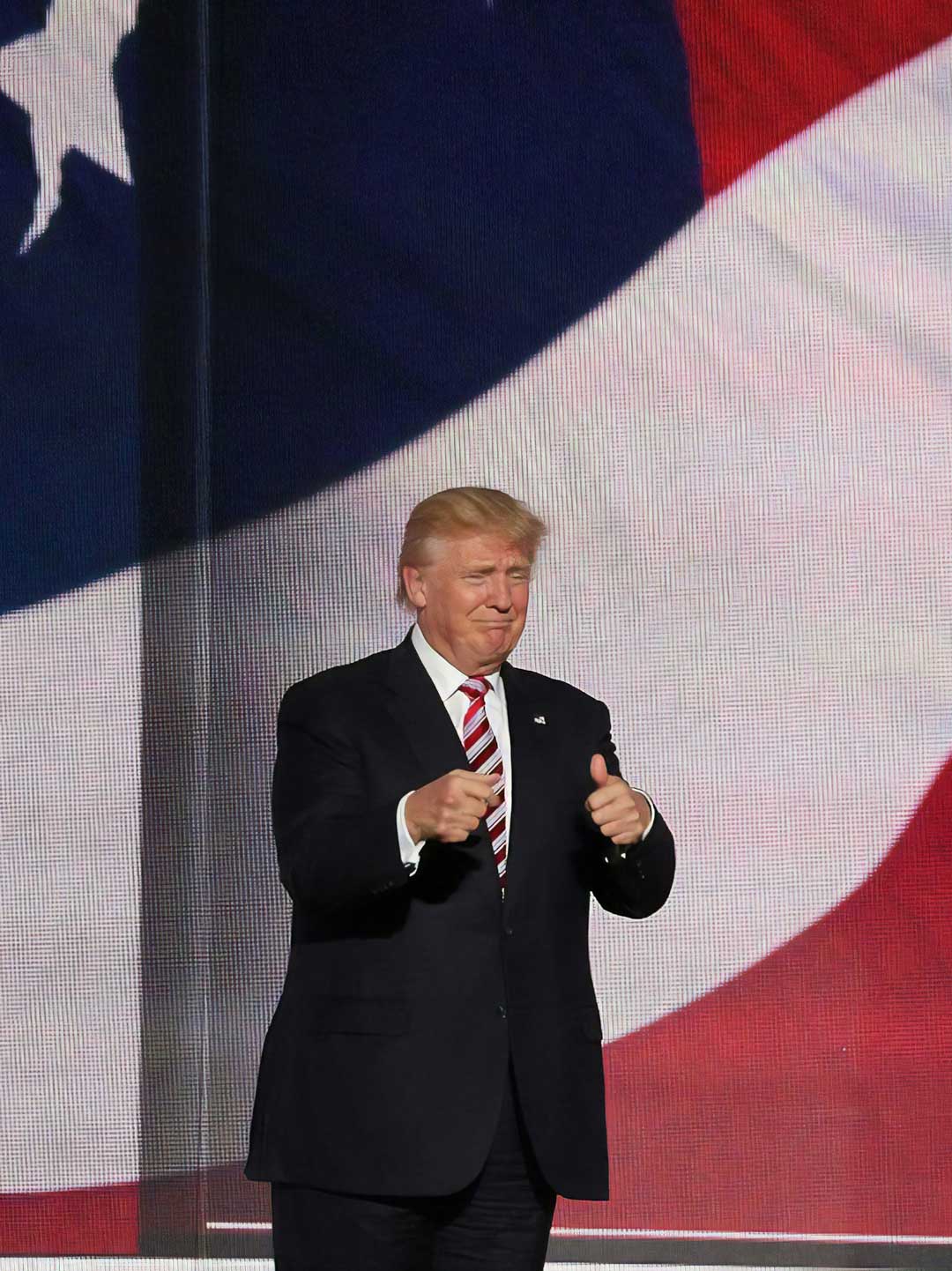

As President-elect Donald Trump prepares to take office, his administration is expected to confront a new norm in US-China relations: ongoing economic warfare. But even in the midst of this likely economic confrontation, there appears to be one overriding goal – to avoid military conflict, particularly in sensitive regions such as the Taiwan Strait or the South China Sea. For Mr Trump, the risks of military engagement with Beijing far outweigh any potential gains. But why is this so critical?

The pitfalls of military conflict

Recent history shows that nations facing territorial disputes with China, such as Russia and India, have opted for peaceful solutions, recognising the economic benefits and avoiding the humiliation of military defeat. For the US, however, the stakes are even higher. Relying on traditional defence systems such as aircraft carriers – designed nearly a century ago – leaves American military assets vulnerable to China’s advances in hypersonic missile technology.

Incoming Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth highlighted this concern, noting that the Pentagon has long warned about China’s rapid development of hypersonic missiles. These weapons could potentially neutralise America’s carrier strike groups within minutes. As Hegseth said in a recent interview, “If 15 hypersonic missiles can take out our 10 aircraft carriers in the first 20 minutes of a conflict, what does that look like?” (Source) This vulnerability mirrors Russia’s early setbacks in Ukraine, where military miscalculations led to both strategic failure and reputational damage. For the US, such missteps would jeopardise not only military credibility but also the global dominance of the dollar – an asset far more integral to American power than mere military reputation.

Economic leverage versus military might

The US’s overwhelming nuclear deterrent has historically failed to produce decisive results in conflicts such as Vietnam or Afghanistan. A nuclear exchange would be catastrophic, especially for a capitalist system dependent on financial stability. Unlike authoritarian regimes with less to lose, a US administration led by billionaires like Trump and his allies cannot afford the economic fallout of a nuclear confrontation.

China, by contrast, has thrived in a peaceful, trade-driven global environment. Its focus has been on maintaining overwhelming conventional and nuclear deterrence to prevent any potential US military intervention. This context suggests that the Trump administration could pressure allies – geographically and economically close to China and Russia – to strengthen their own defence capabilities, thereby supporting the American defence industry without escalating US military spending. However, persuading allies to undertake such costly initiatives in the absence of a pressing regional conflict, such as the war in Ukraine, will be a major diplomatic challenge.

The cost of ally support

Germany provides a stark example of the difficulties involved. Building up its military to support a potential US conflict with China or Russia would require a substantial increase in defence spending, well beyond the 2% of GDP target. Moreover, Germany’s economic ties with China, both as a supplier and a customer, would suffer enormously. A Roland Berger study commissioned by the BDI found that a ban on Chinese lithium exports alone could cost Germany up to €115 billion in value-added production – 15% of its entire manufacturing industry. (Source)

So what could the US offer Germany in return for such sacrifices? Economic decoupling from China would result in severe economic losses, exacerbated by inflationary pressures and rising interest rates triggered by Trump’s proposed 60% tariffs on Chinese imports. These measures would generate short-term tax revenues, but undermine the broader economy and US fiscal stability.

It’s worth recalling why staunch anti-communists like Nixon, Kissinger, and George H.W. Bush initially sought to engage with Beijing and enable the global rise of “Made in China.” Their goal was to solidify the dominance of the U.S. dollar and successfully conclude the Cold War against the Soviet Union. But can the dollar’s supremacy endure in a stagnating global economy without China—especially when pension funds and broader economic stability increasingly rely on growth in markets beyond the G7?

China’s strategic warning

China has already sent a clear signal to the incoming Trump administration. On 13 November, Beijing issued $2 billion in dollar-denominated bonds, attracting more than $40 billion in bids – a 20-fold oversubscription. Notably, these bonds were marketed in Saudi Arabia rather than in traditional financial centres such as London or New York. The message was unmistakable: China’s ability to support the dollar within its geopolitical and economic sphere remains strong, provided Washington respects Beijing’s interests.

This bond issue is both a gesture of cooperation and a warning. By flexing its economic muscle, China is signalling its willingness to maintain the dollar’s dominance, but only on terms that align with its strategic priorities. The Trump administration must carefully navigate this balancing act, recognising that economic warfare with China has global implications far beyond the bilateral relationship.

In sum, while economic conflict may define US-China relations under Trump, avoiding a catastrophic hot war remains a shared imperative. For both nations, as the number one financial and manufacturing power respectively, the stakes – economic, military and geopolitical – are simply too high to risk open conflict damaging their unique and competitive business models.